I’ve been shipping apps to the App Store for well over fifteen years now, and although there are App Review horror stories aplenty, I’ve always hoped I’d never be in a position to write one myself. Fifteen years isn’t a bad run, at least.

Another post chock-full of technical snippets and stories from the app’s development over the past year is coming very soon, and will be a lot more positive than this one. I’m really proud of what we shipped, and this App Review experience doesn’t change any of that.

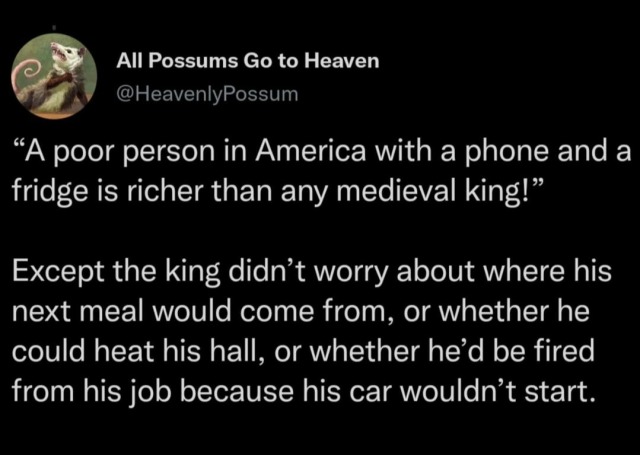

Alright, let’s dive in. They say a picture says a thousand words, so how about a picture of some words. Get those scrollin’ thumbs ready!

What you just scrolled past was the history of my (eventually successful) attempt to get the new Mac version of our app — Cascable Studio — approved for the Mac App Store. The entire process took nearly a month, and we had to push an emergency build through in the middle there with some features stripped out to get something approved for launch.

We’re at version 7.0 now, and the iOS version of this app has been on the App Store since 2015. Indeed, most of the app was fine — this ordeal was all about one particular feature.

A feature that’d already been approved and on the App Store since 2019 in a different app of ours.

Contents

- The Troublesome Feature

- A Core Part of the Mac Experience Meets the Mac App Store

- Coming Off The Rails

- Failure #1: Escalation Is Difficult and Slow

- Failure #2: App Review Appears To Be Missing Critical Information for Mac Submissions

- Failure #3: Rejection Communication is Often Missing Actionable Information

- Failure #4: There Are Frustratingly Few Technical People in App Review

- One Week Later: My Thoughts

- Silver Linings

- Ramifications for the Future

The Troublesome Feature

Our plan was to discontinue an old Mac app of ours called Cascable Transfer and replace it with the Mac version of Cascable Studio. Transfer was a simple but effective app, and Studio supersedes it entirely — it’s far more powerful. Transfer was originally approved for the Mac App Store in 2019.

As part of that work, we brought a Mac-specific feature over to Studio because, frankly, it’s a great feature, and quintessentially Mac: direct integration with other apps. Rather than copy images to a folder with our app then open them in another, why not pass the images directly to other apps?

Here’s how it works with the wonderful Retrobatch batch processing tool:

-

Make a workflow in Retrobatch to, for example, make two versions of each image processed — one at 50% scale with a text overlay that goes into a “Previews” folder, and the other is a straight passthrough into an “Originals” folder.

-

In Cascable Studio, connect to Retrobatch and point it at the workflow you just made.

At this point, you can now drag images from your camera to Retrobatch in Cascable Studio, and it’ll copy the images from the camera and pass them straight through to that Retrobatch workflow… and presto! You have a big pile of processed images.

However, where this feature gets really magic — and really into what makes the Mac great — is our app’s ability to build a pipeline for automatic transfers. Link your camera to Retrobatch in our app and suddenly every time you take a picture it’ll be transferred over to Retrobatch and processed. Point your Retrobatch workflow at a cloud-synced folder and bam! Shutter to cloud in, what, five seconds?

Cascable in the background is configured to automatically pass images from the EOS R5 storage location (a camera’s SD card) to the Retrobatch workflow in the middle, which scales them, adds a watermark, and saves them to the folder open in the foreground. The processed images land in the folder 3-4 seconds after the camera’s shutter button is pressed.

Forgive the sales pitch, but I love this feature and it’s why I love the Mac. This interoperability is a core part of the Mac experience and has been since at least the 1990s — well before Mac OS X.

This deep love of this sort of thing is why I fought so hard for this feature.

A Core Part of the Mac Experience Meets the Mac App Store

Alright, so it’s a great feature. Why was App Review so upset?

Part of why this ordeal was, well, an ordeal is that I was never actually explicitly got a straight answer on that. But we’ll get to that.

For an app to be on the iOS or Mac App Store, it has to be sandboxed. In its default configuration, the sandbox completely isolates an app from the outside world and other parts of the system. If you want to communicate outside the sandbox, you need to declare entitlements, which are specific doors in the sandbox that let you communicate with the outside world in that entitlement’s manner.

As some basic examples:

- To talk to the internet, you need the

com.apple.security.network.cliententitlement. - Bluetooth is

com.apple.security.device.bluetooth. - Using the device’s camera needs

com.apple.security.device.camera.

…and so on.

Some entitlements are so common (like the internet one) that they never really get questioned. Others, App Review will tend to want an explanation and/or demo of their use. This is all fair enough, I guess.

This whole ordeal was over some less common entitlements:

-

To communicate with Retrobatch (and other apps), we use a technology called Apple Events. Apple Events underpin AppleScript as an Apple-provided technology for inter-app communication and scripting — it’s been around almost as long as the Mac has. To use Apple Events from the sandbox, you need to declare the

com.apple.security.temporary-exception.apple-eventsentitlement along with a list of apps you want to communicate with. -

We also have an integration with an app called Capture One, which as a grossly simplified explanation is “like the Photos app, but for professionals”. With our integration, the user can add photos directly to their Capture One library. For various technical reasons, when attempting to export images to Capture One, the user would see a rather scary dialog about Capture One “accessing data of other applications”. To work around that, we used the

com.apple.security.temporary-exception.files.home-relative-path.read-writeentitlement to temporarily place exported images outside of our sandbox during the export so the user wouldn’t see that scary dialog.

This is a screenshot of what the relevant entitlements look like in Xcode:

Coming Off The Rails

Now I’m out the other side, I think what happened here were a combination of procedural failures — combined with some unfortunate timing — that coalesced into a nearly month-long review process. Rather than take you through the slog that I did, I’ll instead split out my experience into the explicit ways I think App Review failed here, and ways they should do better in the future.

We usually submit major updates well in advance of the planned launch date, because there’s always stuff to work through with App Review. This time, we submitted a little under three weeks before our target date of December 5th. As a quick timeline, a lot of which isn’t shown in that screenshot above:

| November 16th | Initial submission. |

| November 17th | Initial rejection, flatly denying the use of all of the "less common" entitlements described above. I ask for a call from App Review. |

| November 25th | I received the call, and was advised to explain the entitlements to App Review but "not to expect any movement for a week due to Thanksgiving". I inferred that the Apple Events entitlements "should be" OK, but it'd need to be escalated. |

| November 29th | Got nervous about the lack of any movement, and pulled the build to resubmit with the feature stripped out. |

| November 30th | Rejected pending information for why we use the Bluetooth, Camera, and Location entitlements. |

| December 1st | Resubmitted. |

| December 1st | Rejected pending information for why we use the Network Server entitlement. |

| December 1st | The build with the feature stripped out was approved. |

| December 2nd | Re-submitted with the feature reinstated. |

| December 3rd | [Luck +10] I attended an App Review lab, and connected with a very nice App Review staff member that was able to look into what was going on for me. Said that it was being looked at in more detail. |

| December 4th | Rejected with an identical rejection to the one on November 17th and a weird additional rejection about our paywall. That same paywall was approved three days prior on both Mac and iOS. |

| December 4th | [Luck +10] Ripcord pulled: I managed to find a relevant person with decent seniority in the right department. I emailed that person and got a "We'll look into it" reply fairly quickly. |

| December 4th | I receive a notice that this is now being looked at by the appeals board. |

| December 4th | I receive a message from the appeals board asking for information on why we're using the less common entitlements identified above. |

| December 5th | Launch day! I launch with this feature missing from the Mac app. |

| December 9th | I receive a follow-up call from the staff member I met in the lab. We scheduled another call for a few days' time to see how the progress was going with the new submission. |

| December 10th | I receive an almost identical rejection to the ones on November 17th and December 4th, the message for which contradicts itself. |

| December 10th | I reply to the rejection pleading for a straight answer. I get told "We advise submitting a revised binary with your suggested changes for review." |

| December 10th | I resubmit without the com.apple.security.temporary-exception.files.home-relative-path.read-write entitlement. |

| December 11th | Rejected pending information for why we use the Bluetooth entitlement. My reply is… snippy. |

| December 11th | Approved! |

| December 13th | I receive a follow-up call from the staff member I met in the lab. We chatted about the past few weeks and I gave some feedback to hopefully pass along. There's still one outstanding question on whether App Review can see some details in the submission form. |

| December 16th | I receive a follow-up call from the staff member I met in the lab. We chat a bit more about that outstanding question and conclude the "incident ticket", as it were. |

Yikes.

Failure #1: Escalation Is Difficult and Slow

When you get rejected by App Review, you’ll get a message about why and the ability to reply in text form. Sometimes, rejections are simply requests for information, but there’s always the ability to reply — even if the rejection wasn’t asking for information, a review can sometimes be turned around without re-submitting if you “Um, actually…” them if they got something wrong.

I have no insider information about how the review process works, just fifteen years of outside observation. From my observations, the reject-reply-action turnaround can be fast if the person reviewing the app has the power to continue the review with everything they then have (although it can still be a dice roll — “Will this be actioned in ten minutes or two days?” is still a thing). In my experience this doesn’t include anything regarding policy - i.e., if someone needs to take context into account to make a decision, you’re out of the “fast” queue.

My experience also supports the fast queue being somewhat international and running 24/7, but once you’re out of that you’re limited to progress being made in California business hours — and timescales start being measured in days and weeks.

In my instance here, I got rejected on November 17th, and I asked for an escalation and a follow-up call the next day. I got a reply a little over a day later confirming that the call would come in “3-5 business days”, and the call arrived on November 25th. The person on that call was basically collecting more information from me so the issue could then be escalated.

Unfortunately, this was Monday on the week of Thanksgiving, and I was told that realistically I wouldn’t be seeing any movement until the following week due to that.

Even ignoring the bad timing of Thanksgiving (and the fact that it seems the entire department shuts down for a whole week?), that’s a week between asking for an escalation and getting it. That’s a long time of nothing.

Failure #2: App Review Appears To Be Missing Critical Information for Mac Submissions

When you submit a Mac app, you get an extra section in the submission form entitled “App Sandbox Information”. In that section, you add all of the entitlements you’re using from a drop-down menu and explain exactly what you’re using each entitlement for. I made sure to fill out that section diligently, and here’s what ours looks like for Cascable Studio:

We got rejected or asked for missing entitlement information multiple times during this process — on November 30th (Bluetooth, Camera, and Location), December 1st (Network Server), December 4th (Apple Events and file access from the appeals board), and December 11th (Bluetooth, again). It wasn’t stated explicitly, but I was told that missing entitlement information was a factor in the initial rejection on November 17th, too.

In all of these cases, we had provided detailed information about why we’re using the entitlements in the mentioned section of the form. In all of these cases (bar one where the entitlement was included in error, and a more detailed explanation for the appeals board), I copy and pasted the information I’d already written from the form we submitted to App Review into the reply to App Review. The reviews then continued.

I must admit, I was particularly snippy about the second Bluetooth one:

We have already explained, in exquisite detail including with a demo video, why we use Bluetooth in this app earlier in this very same submission process. Please review the earlier correspondence for those details. If you are unable to scroll up far enough, I’ll repeat that information here:

You can also see that video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UVxAIF2eGUs

(Text explanation of what’s happening in the video)

In all of the “live” conversations I’ve had with actual Apple employees (three separate conversations with two separate people), they were not able to see this additional entitlement information. I was told that they don’t necessarily have the same tools the actual reviewers do, so what they see might not match.

This happened often enough that it goes beyond a simple oversight by an individual reviewer. Either they can’t see the provided information, or they’re not aware that it’s there.

Update after I wrote this but before I published it: I received a final follow-up call and I was told that for now, the advice is to duplicate entitlement information into the “Review Notes” field. There seem to be no straight answers to be found anywhere about whether App Review can see these additional fields, even internally.

Entitlement information is critical information to perform a review of an app. If App Review can’t actually see this information in Mac submissions, this is a serious failure of the tooling for this process. If the reviewers can’t see the information, how can they possibly review the app properly?

Failure #3: Rejection Communication is Often Missing Actionable Information

After weeks of back-and-forth and waiting, the final conclusion is that the problem was with the com.apple.security.temporary-exception.files.home-relative-path.read-write entitlement — the Apple Event ones all got approved once that was taken away.

However, that was never explicitly stated in my rejections. Even after going through the appeals board, I got this rejection:

Thank you for your patience.

Regarding 2.4.5, we found that the app may not use the following entitlements:

com.apple.security.temporary-exception.apple-events

(A list of all the Apple Events entitlements)com.apple.security.temporary-exception.files.home-relative-path.read-write

/Library/Caches/Cascable Capture One Exports/To resolve this issue, it would be appropriate to adhere to the following provided guidance:

When sending an AppleEvent with the proper types (e.g.

typeFileURL), then the receiving application will be granted access to the specified data without having to move/copy the file to a shared location such as the cache.If you continue to have issues with that mechanism, please submit a Radar against it.

If we boil this down, this message says:

You cannot use Apple Events. You cannot use the shared cache location. When sending an Apple Event with the proper types, you don’t need to use the shared cache location.

…which is a very contradictory trio of sentences. I asked for clarification:

…can you please make a clear judgement regarding Apple Events? Your message contradicts itself.

You wrote:

“We found that the app may not use the following entitlements: (list of Apple Events entitlements)”

Then you wrote:

“When sending an AppleEvent with the proper types…”

So, which is it? Are we not allowed to use the Apple Events entitlements, or is it just the cache directory usage that’s the problem?

I got the reply:

We advise submitting a revised binary with your suggested changes for review.

Would it kill them to give a straight answer? I get that they don’t want to put anything in writing because people like me publish blog posts like this one putting their words out for the entire world to see, but I really can’t possibly see how “If you take away this entitlement, these other ones are OK in your particular use case” is a damaging statement to make.

That information — that the Apple Events entitlement should be OK without the other one — did appear to be present internally almost from the beginning. It was implied on the call I received on November 25th, and if you read between the lines in that rejection above on December 10th it’s kinda-sorta there too.

However, I can’t run a business on inferring from indirect statements and reading between the lines. This process sits between my business and its revenue, and I need to be sure where we stand. I appreciate that they can’t pre-approve an app idea, but when we’re three weeks into a back-and-forth and we’re talking about a very specific feature in a very specific app submission, “we advise submitting a revised binary with your suggested changes for review” is kinda horseshit. So I get to spend engineering hours implementing something to find out if I’m reading between the lines correctly? Yuck.

Failure #4: There Are Frustratingly Few Technical People in App Review

Now. I will grant that Apple Events are a fairly low-level technology. It’s also a very old one — when looking up documentation for Apple Events to give to App Review to show it’s a public Apple technology, I found a document with this diagram in it:

It’s aged delightfully, but I figured showing App Review a diagram from the ’90s was unlikely to help the case that it belongs in the modern App Store.

Anyway, I must’ve explained what Apple Events are to three separate people throughout this process. This did eventually get to someone technical up at the appeals board, but nobody having any idea what an “Apple Event” is really cannot have helped.

It wouldn’t be a blog post without at least one meme.

I do understand that they don’t need to hire programmers to reject apps for bad screenshots or whatever, but if App Review can’t understand the technologies at play when they’re reviewing apps, how can they possibly review the app properly?

One Week Later: My Thoughts

This is now a story I’m writing a blog post about and not one I’m living. It was very stressful to live through — I’m sure I’ve lost some years from my life over all this, and Apple’s larger policy of “no communication until we feel like it” is extremely not helpful. Squeezing in a build with the feature stripped out so we could launch when planned did lessen the load a bit, but it meant that one of the release’s best features was completely absent from the launch’s press material — a huge blow to marketing visibility.

It’s a shame, too — this release was the result of more than a year of work and was the most ambitious launch in the history of the app. It should’ve been a momentous and happy day, but there was a huge cloud put over it because of all this. Alas, three weeks’ lead time on our App Store submission wasn’t enough. I hate to think how long it would’ve been (or if we’d have got an approval at all) if App Review didn’t happen to be hosting labs, and if I didn’t manage to find the contact details of someone to escalate to.

Now, I’m not one of those people that’s morally opposed to app review as a concept (as long as there are alternative distribution options, which is the case on the Mac, at least), but it has to function correctly.

I’m not even that upset about some of the rejections I got during this process. When App Review works well, the back-and-forth is fine. If we ignore the larger chaos here and look just at the rejection on December 11th:

| 9:23 am | Rejected needing information on why we use Bluetooth. |

| 9:56 am | We reply with the requested information. |

| 10:05 am | In review. |

| 10:08 am | Approved. |

That sort of back-and-forth with that sort of turnaround time is fine. They’ll sometimes genuinely need information, and taking that and immediately acting upon is a perfectly reasonable process - which also mitigates situations where they’re asking for information they already have.

What isn’t OK is:

- App Review not being able to see — or not being trained to look for — critical information for the review process.

- Turnaround times measured in weeks.

- The entire process shutting down for a whole week due to Thanksgiving.

- Never being able to get a straight answer, receiving conflicting information in a single message, and having to infer and read between the lines.

- Me having to schedule my big submissions around times when App Review happens to be hosting labs so I can actually get a human to speak to.

- Me having to desperately try to find contact details for someone I can escalate things through on any sort of reasonable timescale.

This has to be better. A lot of it points to a department that has to deal with millions of app developers and submissions without the resources to do so well when things fall out of the “optimised path” like this did. Of course, that defence immediately falls apart when you notice that Apple is one of the richest companies on the planet (not that you can throw buckets of money at every problem to make it disappear, but still).

Silver Linings

I do try to make an effort not to complain all the time, so let’s find some positives:

#1: The amount of support I got from the community really helped. Being an indie developer is a uniquely… er, unique? experience — especially on platforms with a monolithic gatekeeper like the App Store — and when things like this happen there’s a little pit of existential dread that forms while you feel like your business hangs on the whims of some people in a meeting room somewhere*. There’s only so much empathy most of my “IRL” friends and family can have for that, and having a big pile of peers cheering me on and otherwise sharing in my experience made things a lot easier to bear.

* Obviously this isn’t a rational reaction to what was happening here — the loss of that feature wouldn’t actually be a death knell for my business. Still, when you build a feature you’re excited about because it’s a great fit for the platform you’ve been using for 30 years, only get a flat Nope. from the gatekeeper without additional context, there’s suddenly a disconnect between what you thought the platform was about and what the gatekeeper thinks the platform is about. That’s not a nice feeling.

This particular little snippet from a community I’m in made me laugh a lot, so I thought I’d include it here (with permission):

#2: Connecting with an App Review staff member in the App Review labs was a godsend. They didn’t work directly on reviewing apps so it’s not like they could just go in and approve the app, but they were able to see things I couldn’t and ask questions internally that I couldn’t. Getting this additional context — and someone on the inside able to shout for me — at least kept hope alive when my “official” communication from App Review was so devoid of… well, anything. When they didn’t know an answer to a question they promised to find out and follow up with me, and they did so every time. They did an excellent job given the restrictions they had (i.e., not having a giant “Approve” lever they could pull).

Hopefully these App Review labs (which are listed here on the Apple developer site - search for “App Review”) are a continuing and consistent thing, because they offer a much-needed lifeline.

Ramifications for the Future

So, what now? While we do have the feature approved and in the App Store now, this ordeal has affected my outlook for the future quite significantly:

Cascable Studio

It’s likely that, even though the app is approved now, I’ll pull the Apple Event stuff out and into a separate downloadable component that’s outside of App Review’s purview. I’d like to integrate Cascable Studio with more and more apps in the future, and I very much don’t want to go through this argument again any time soon.

This solution is perfectly achievable with sandboxing intact and without any funny business that’d affect App Review, but it is a worse experience for the user and a lot more effort on our part. It sucks for everyone, but it’s better than doing this every time — or even having the shadow of this maybe happening again on every submission.

Our Other Apps

We have another Mac app — Cascable Pro Webcam — that’s currently being sold outside of the App Store. When I first made the app, virtual webcams were flat-out not allowed on the App Store, which to be honest was fair enough — the architecture for virtual webcams at the time was extremely not secure.

However, since then Apple has shipped a new architecture for virtual webcams that Pro Webcam implemented immediately. Now it’s allowed, I was planning on moving Pro Webcam to the App Store with its next major update in the new year — we’re currently using Paddle, and I’m not very happy with them. However, it also uses a “non-standard” entitlement (com.apple.developer.system-extension.install), and after my experience here I’m seriously reconsidering that plan.

Further Into The Future

This ordeal has rekindled my uneasiness of being reliant on a single gatekeeper for my company’s survival. Yes, we can ship on the Mac outside the App Store, but still.

Being multi-platform has been at the back of my mind for a long time, and at the beginning of the year I did a decently-involved investigation into using Swift on Windows. I find my desire to return to that suddenly getting stronger, for some reason.